Groups vs. teams: 7 attributes that distinguish teams from groups

What exactly makes a team a team? How do you distinguish groups vs. teams? You might believe you have been part of a professional team and practiced true teamwork. The tragic truth, however, is that most people never experience true teamwork. They usually work in artificially drafted groups of lone warriors, mostly in parallel instead of with each other and for each other.

However, actual value creation in a professional organization requires genuine teamwork. We need teamwork that is worthy of the term team. Organizations that cannot distinguish group work from teamwork will never be able to excel and outperform the market. In addition, many of the currently popular (and widely abused) agile concepts for professional organizations, like Scrum or Kanban, rely on true teamwork to be efficient.

But how exactly do you distinguish teamwork from group work?

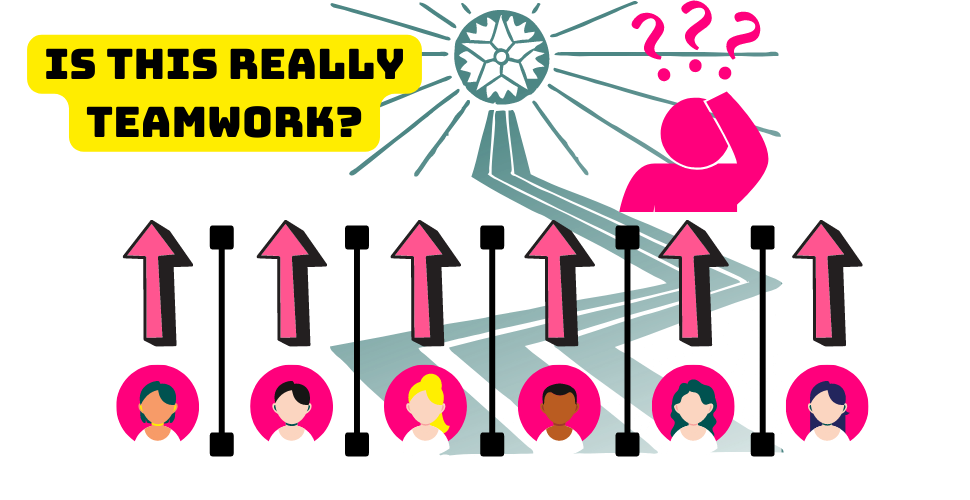

TRADITIONAL (GROUP) WORK

In most professional organizations, people work in parallel to achieve an outcome. They break work into supposedly valuable small chunks based on disciplines and then distribute them to specialized sub-groups or individual experts. These designated group members are supposed to finish their piece of the overall work puzzle according to strict, seemingly well-working processes. They occasionally come together to exchange status, try to align, and then leave to do their own thing. This artificial way of working shouldn’t be confused with teamwork but, instead, be correctly labeled group work.

Exercise: puzzling in groups

Have you ever started and finished a puzzle before? Probably the answer is yes. You might remember how often you usually look at the final picture while doing the puzzle. Now imagine there are four puzzlers, and the puzzle has been separated into four areas. Your task is to finish exclusively your designated area. You are not allowed to look at the final picture most of the time. Only during dedicated occasions are you and your fellow puzzlers coming together to look at the whole picture. Solely during those moments are you allowed to exchange puzzle pieces that you think you don’t need for your area. What do you think: How efficient is this method of group puzzling, and how long would it take you and your co-puzzlers to finish a 1000 pieces puzzle? Let me know in the comments!

How to identify a group

But how do you know if you are part of a team or a group?

The following attributes will give you an idea of how to identify groups vs. teams. Usually, identifying one or two of these behaviors or attributes is sufficient to be sure.

- Contradictions

- The group’s missing shared, self-imposed identity and purpose inevitably lead to contradictions. Most groups don’t even know their sphere of activity, and if asked, they usually think it is too vague (“Finish this project!”) or too complex (“Make this customer happy!”).

- Separation

- the division of work packages into individual functions owned by separated disciplines. These functional work silos each follow their conventions. Each silo hands off results based on very detailed interfaces.

- Central steering

- the concept of decision-making in central locations, far away from the situation. Groups rarely decide something. Usually, a group escalates controversial decisions. They translate and delegate them up the chain of command.

- Short-lived

- the constantly changing composition of team members. Organizations form and resolve groups continually by design.

- Unrelated size

- the number of group members is usually high, often exceeding ten people. Groups often proliferate because their sphere of activity requires additional people. The concept of siloed work requires particular, trained experts. Groups usually try to solve delays (most often due to central steering) by bringing in new people.

- Diverse levels of mastery

- the level of the group members’ mastery is vastly different. Once groups swell (see #5), they usually become very diverse in the level of mastery of their members: from beginners to experts; there is a broad range of abilities.

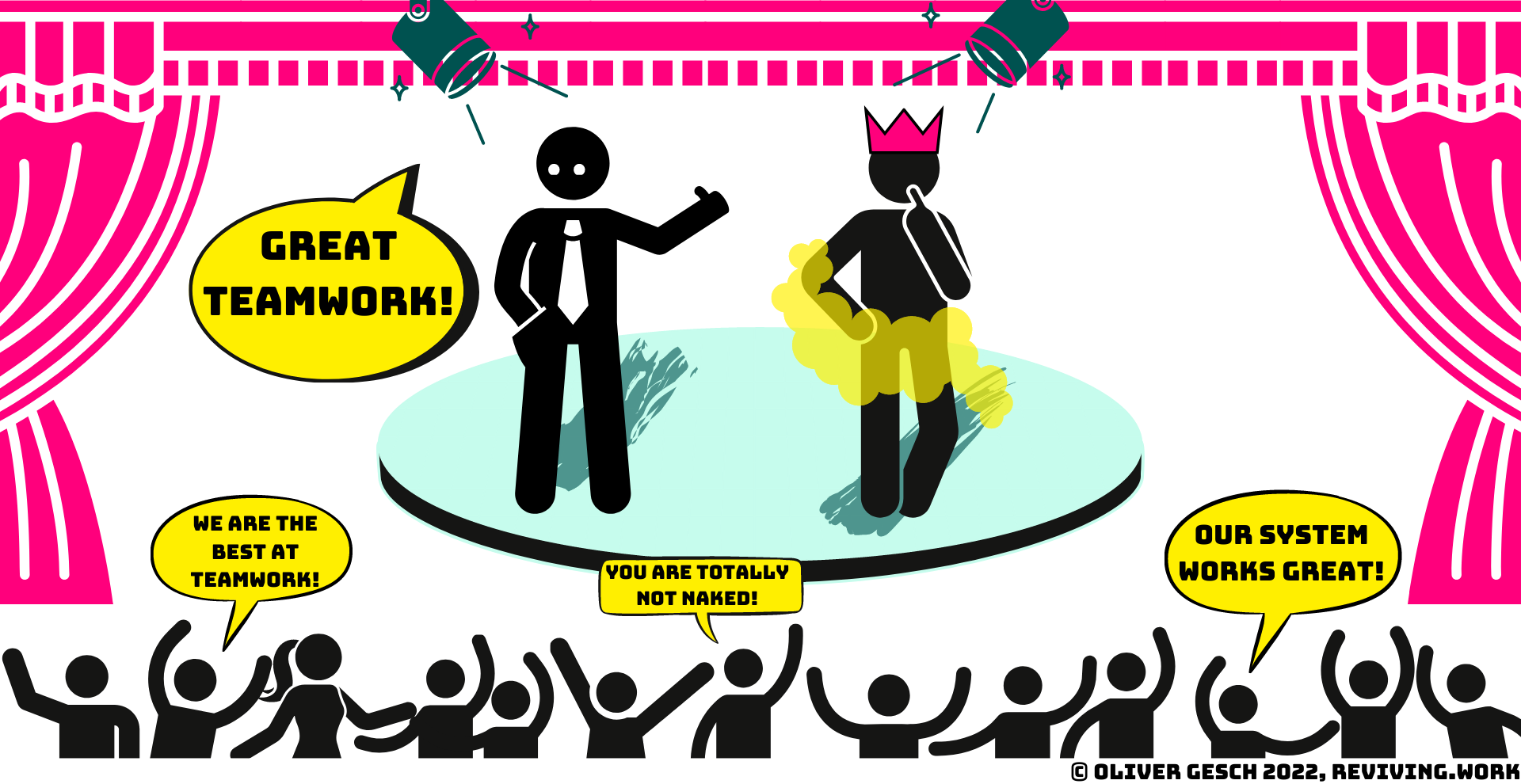

Groups are often mislabeled as teams

Just like in Andersen’s The Emperor’s New Clothes most of us, especially so-called management experts, believe an organizational concept that shows these six attributes can still be called teamwork. Naturally, some might recognize the naked emperor right in front of them as what he is: naked. However, nobody wants to tell the emperor that he is simply naked and actively scammed. Everybody feels pressured by the supposedly well-thought-through system of traditional management. No one wants to admit

- that what this organization does is not teamwork,

- that this doesn’t feel right

- that there is no flow,

- that this is not a natural, organizational concept,

- that the system is broken and individual, absurd behavior is a direct result.

Usually, no member of the organization calls this out. People quickly become defensive when told: “You are not working in a team; you are not doing teamwork!” Based on observations of the systemic characteristics above, it does not matter if this is an objective fact. Most people consider themselves team players, and seemingly denying them this attribute suddenly results in tremendous affront.

At least the experts should know and do better. However, consultants will also not call this out because they usually want to sell any of their off-the-shelf one-fits-all packages. Telling the customer that their way of working together has to change fundamentally would just prolong the sale. It does not serve their business case to question fundamental beliefs or even mention the common misinterpretation of groups vs. teams.

In the end, everybody eventually recognizes that this way of working does not feel like teamwork compared to, e.g., a sports team, but no one is willing to bring this up. Nobody wants to be the outsider who does not consider this organizational concept “teamwork,” and nobody has the incentive to do so. The established, broken system causes this problem. It is much easier to let the emperor stay naked and imagine his clothes to be invisible. People eventually will become frustrated when encountering such inconsistencies in their organizational systems. They might start behaving differently, feeding the misconception of Theory X employees.

TEAMS: NOT A HOPELESS CASE

But how is teamwork different?

There are countless definitions of teamwork in the standard literature; however, one defining characteristic covers it all: Emergence. Emergence is that special something, that “je ne sais quoi” that is difficult to describe. One way to define it is as follows:

“The System is something beside, and not the same, as its elements.“

Paul Martin

This definition is based on Aristotle’s “the whole is something besides the parts.” It implies that one cannot predict a resulting system’s characteristics based on knowing the combination of its parts. This insight is crucial to understanding the value of a team compared to a group.

We can distinguish between team performance increasing and team performance decreasing emergence. Cultivating the former and preventing the latter is a matter of creating the right circumstances and environment.

The primary enabler of performance-increasing emergence is a firm belief in human nature based on Theory Y. You need to ensure that this fundamental insight is the universal foundation for every decision you make. Your teams will never achieve genuine performance-increasing emergence, and their performance will deteriorate and eventually collapse without this foundational insight.

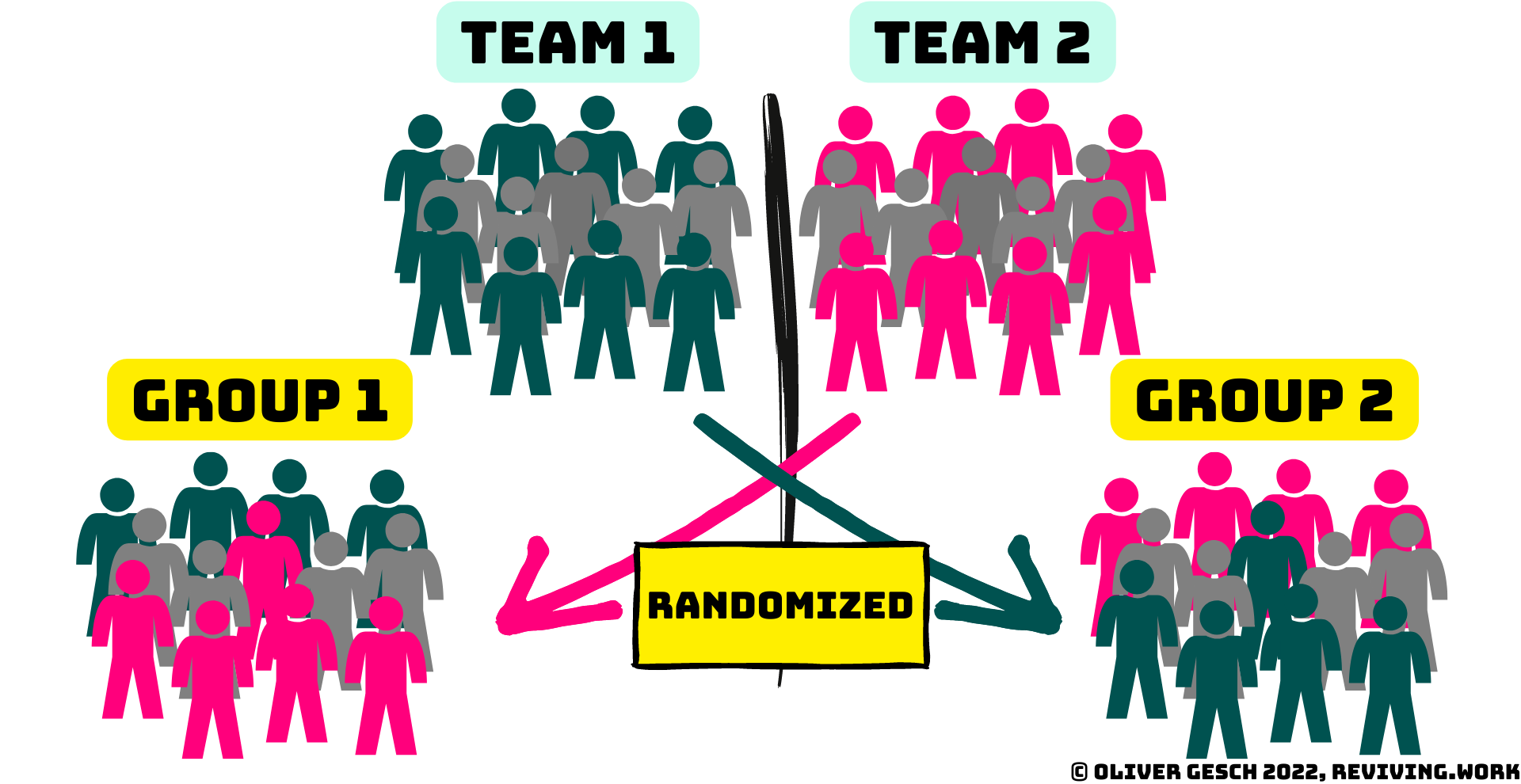

Emergence thought experiment: football teams

Imagine two equally high-performing, well-established football teams with equally high-performing individual players. Now let’s imagine you randomly assign each player to one or the other team. Would the two resulting teams play as well as the original teams? Probably not, because the team is something else than just its combined parts. Putting together well-trained and highly skilled players does not make a successful team. Becoming a high-performing team requires more than qualified members.

The 7 critical attributes of genuine teams

But what exactly distinguishes teams vs. groups of people, teamwork, from working in groups? You will find countless opinion pieces and research online on this subject; however, most arguments will include any combination of the following core attributes:

- Diversity

- a diverse composition of people from different backgrounds, experiences, and environments.

- Autonomy

- a sufficiently independent sphere of activity that can be mastered by the team autonomously. Teams know exactly who their customers are and how to satisfy their needs autonomously.

- Integration

- the integration of required functions based on roles instead of separation based on silos. Teams integrate most of the necessary functions as part of their joint mastery and skillset.

- Self-organization

- the authority to make decisions in direct proximity to the situation. Teams have the authority to identify the best way to achieve the desired outcome without external interference.

- Longevity

- the appropriately chosen minimum duration, a team should not change the majority of its members. Team members join a team semi-permanently.

- Suitable Size

- the number of team members, between 4 and 10, preferably between 5 and 7. Teams make sure their size is appropriate to their sphere of activity.

- A similar level of mastery

- the compatible level of expertise and mastery among team members. Teams form around individuals with comparable levels of mastery.

Some people might argue that certain teamwork traits also apply to group work. While that might be true, it is usually not sufficient for the formation of a high-performing team to aim for just some of these characteristics. If you miss just one attribute, the complex system that makes up a team might never develops in the first place or eventually deteriorates.

WHY TEAMS OUTPERFORM GROUPS

Let’s take a look at some of the dynamics and effects of teams vs. groups that lead to superior performance:

- Achieving individual, personal outcomes is frequently not the same as a group of people achieving their desired group outcomes. The concept of separating work into smaller, distributed chunks is based on the premise that everyone knows everything up front. Work and process descriptions are flawless, and results will fit perfectly. This premise is often untrue, and successful individual outcomes don’t result in overall success.

- Teamwork puts the outcome, the team’s goal, and the actual value creation above individual goals. The team readjusts its activities constantly to make sure that the team is successful together as a whole.

- Aligning after extended periods of individual work requires the time and effort of the group. They must learn each person’s work history from the last touchpoint to now.

- Teams work with each other all the time. They often meet daily and work in pairs or even more prominent formations. This way of working reduces any need for extensive alignment drastically. The team aligns itself continuously.

- A group does not make consequential decisions autonomously. Instead, someone creates a separate forum where people with more formal power (usually middle management) from each discipline come together. Most often, these manager forums are also unable to agree quickly to make decisions because of: 1) a lack of understanding of the subject matter, 2) no common understanding of how to make decisions at all, or 3) a missing mandate from their formal leaders.

- Teams, on the other hand, usually contain the required mastery, the close connection to the current situation, and the authority to decide. They decide quickly and constantly whenever needed.

- Organizations usually don’t create Groups around a joint and coherent sphere of activity. Instead, they typically serve a very specific or very general purpose. In the former case, the group suddenly has external dependencies because any genuine progress is measured in larger increments than the particular purpose for which the group was established. The group requires help from additional groups to achieve any meaningful progress. In the latter case, the group also suffers from external dependencies on certain specialists because the group is asked to deliver a very extensive outcome without having all the required functions integrated.

- Organizations form teams with a particular outcome and value stream in mind. They also regularly question their focus, re-sharpen their sphere of activity and re-evaluate their value streams. This self-directed re-calibration results in lean ways of working that reduce waste to a minimum.

- Groups are temporary and short-lived. Most often, people don’t spend the time to put the crucial, foundational agreements in place for the group’s purpose, decision-making process, or roles. Ultimately this leads to different expectations, misunderstandings, and severely delayed decision-making.

- Teams are relatively permanent. People should stay for 12 to 18 months, and overall team churn should stay low. Stable teams increase their performance and their valuable output constantly. At the same time, they prevent wasteful startup phases of newly formed groups.

- Communication channels in a group of people grow exponentially compared to the linear growth of the number of people. This sudden growth means there is frequently no way to address the thousands of parallel communication channels pragmatically. Word of mouth will lead to misunderstandings and re-work. Slow meetings with many people are the norm.

- Preferred team sizes are between 5-9 team members, with a recommendation to stick to the lower end of the range. Fewer people lead to less communication overhead which equals less waste and more valuable output.

- When organizations assign people with very diverse skill levels to the same group, it can lead to frustration on both ends of the spectrum: the people who mastered their trait will be frustrated because the beginners cannot follow. They have to wait for the rest of the group. The beginners will be frustrated because they cannot follow those who mastered their traits and will always be behind.

- Intentionally drafted teams, with comparably skilled team members, can operate comfortably for each team member without losing the contribution of lesser skilled people or having to wait for them to catch up.

These are just some of the most common benefits of working in teams vs. working in groups. You might want to consider many more aspects, depending on how teamwork or group work is implemented in your specific contexts. If you recognize any of the mentioned traits in your local organization, let me know in the comments!

A PLACE FOR GROUPS

One might be wondering if there are situations where group work is more suitable than teamwork in a professional setting. The answer to that question is undoubted: yes, there are. People fulfill many different roles in life and especially in professional organizations. Most of these roles might fit the context of a relatively stable, long-term team. However, some roles might be best suited to a different mode of operation based on groups. Examples include:

- Learning and knowledge acquisition in a specific discipline with equally educated people

- Major, organization-wide decision making

- Solving special, isolated incidents by specialists

Most people will probably become members of several groups, a few hours here or there, for a particular duration while continuing to be valuable and contributing members of their home base: their team.

SUMMARY

Many people still confuse teams vs. groups, teamwork with group work. Especially English-speaking organizations often put together any number of people with a common interest and usually automatically consider this the creation of a team. However, telling people to work together is, of course, as we just discussed, not enough. Teams have a unique characteristic that is not materializing out of thin air automatically if the preconditions are not correct: emergence. This trait is the critical element of a true team that encompasses all of the attributes described above in one single and precise distinction from groups. There might be any combination of characteristics that will lead to performance-increasing emergence in a team. However, there is a high chance that you require many, if not all, of the seven points mentioned above to make it happen.

You might also feel confused because you and your group members get work done just as fine as so-called “teams.” This personal, anecdotal evidence originates in the missing distinguishment between teams and groups. It results from a false baseline of the omnipresent group. If you have never experienced true teamwork, you don’t know how much of your group’s human collective potential is wasted everyday. This unnecessary waste is particularly tragic when you consider all the additional effort people outside your group have to make to keep the group aligned to move in the same direction. Emergent teams will outperform groups practically every time.

Forming a team requires a shock to the system, an intervention. You must overcome the current system with dedication, focus, and intention. You must consider many things, make agreements, and think things through. However, the bottom line is that creating the right circumstances for performance-increasing emergence in a team will be worth it.